Effects of Maltreatment on Brain Development

- Stress

- Persistent Fear Response

- Hyper-arousal & Dissociative Responses

- Hyper-arousal

- Dissociative

- Disrupted Attachment Process

- Neglect & Lack of Stimulation

- Global Neglect

- Pervasive & Long-term Effects

"Harry Chugani observes, ‘We can have individuals who, based on early experiences, are in effect "hard-wired" for negative behaviors.’ Some neuroscientists consider this an overstatement; others find it too mild" (Shore, 1997, p. 40).

Babies' brains grow and develop as they interact with their environment and learn how to function within that environment. When babies' cries bring food or comfort, they are strengthening the neuronal pathways that help them learn how to get their needs met, both physically and emotionally. But babies who do not get responses to their cries, and babies whose cries are met with abuse, learn different lessons. The neuronal pathways that are developed and strengthened under negative conditions prepare children to cope in that negative environment, and their ability to respond to nurturing and kindness may be impaired (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

Stress

Brief periods of moderate, predictable stress are not problematic; in fact, they prepare the child to cope with the general world. The body's survival actually depends upon the ability to mount a response to stress (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). But prolonged, severe, or unpredictable stress--including abuse and neglect--during a child's early years is problematic. The brain's development can literally be altered by these experiences, resulting in negative impacts on the child's physical, cognitive, emotional, and social growth.

Chronic stress sensitizes neural pathways and overdevelops certain regions of the brain involved in anxiety and fear responses, and often results in the underdevelopment of other neural pathways and other regions of the brain (Shore, 1997). Children who experience the stress of physical or sexual abuse will focus their brains' resources on survival and responding to threats in their environment. Children who experience the chronic stress of neglect--e.g., remaining hungry, cold, scared, or in pain--will also focus their brains' resources on survival. This chronic stimulation of the brain's fear response means that the regions of the brain involved in this response are frequently activated. When they are, other regions of the brain, such as those involved in complex thought, cannot also be activated and are therefore not "available" to the child for learning (Shore, 1997).

Because the brain ultimately controls all bodily functions, experiences that alter brain development also alter our bodies' responses. Studies have shown that "the overwhelming stress of maltreatment experiences in childhood is associated with alterations of biological stress systems and with adverse influences on brain development" (DeBellis et al., 1999). One example of the effects of early maltreatment on brain and body functions involves the chemical cortisol. Cortisol is a hormone that helps the body prepare to cope with stress through its effects on metabolism and the immune system (Hart, Gunnar & Cicchetti, 1995). Studies have shown that many infants and children who have been maltreated have abnormal secretions of cortisol, indicating that their bodies' responses to stress have been impaired (Hart, Gunnar & Cicchetti, 1995; Lott, 1998, citing Main, 1996). More research is needed to understand why this occurs and what effect this may have on the children's emotional and social development, but this information provides some evidence of altered brain activity in maltreated children.

A key point to understand about altered brain development in children who have been maltreated is that the way in which their brains develop is often a very useful adaptive response to their negative environment, but it is maladaptive in other environments (Hart, Gunnar & Cicchetii, 1996). If a child lives in a threatening, chaotic world, his brain will be hyper-alert for danger; his survival may depend on it. But if this environment persists, and the child's brain is focused on developing and strengthening its strategies for survival, other strategies may not develop as fully. If a child lives in a world that ignores him, if he is not provided with appropriate stimulation for growth, his brain will focus on survival from day to day and may not fully develop healthy cognitive and social skills (Ounce of Prevention Fund, 1996, citing Lieberman & Zeanah, 1995). The result may be a child who has great difficulty functioning when presented with a world of kindness, nurturing, and stimulation. It is an unfamiliar world to him; his brain has not developed the pathways and the memories to adapt to this new world.

Persistent Fear Response

Fear is necessary to our basic survival. We must be able to detect threats and respond. Indeed, the brain is uniquely designed to sense, process, and store threatening information and to mobilize the body in response to threats. All parts of the brain and body are used in this response. "This total neurobiological participation in the threat response is important in understanding how a traumatic experience can impact and alter functioning in such a pervasive fashion" (Perry, 1999, p.3).

Chronic stress or repeated traumas can result in a number of biological reactions. Neurochemical systems are affected, sometimes causing a cascade of changes in attention, impulse control, sleep, and fine motor control (Perry, 2000a; 2000c). Chronic activation of certain parts of the brain involved in the fear response (such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal [HPA] axis) can "wear out" other parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is involved in cognition and memory (Perry, 2000c). Early experiences of trauma can also interfere with the development of the subcortical and limbic systems, which can result in extreme anxiety, depression, and difficulty forming attachments to other people (Shore, 1997). Furthermore, chronic activation of the neural pathways involved in the fear response can create permanent "memories" that shape the child's perception of and response to his environment. While this adaptation may be necessary for survival in a hostile world, it can become a way of life that is difficult to change, even if the environment improves.

Hyper-arousal & Dissociative Responses

Dr. Bruce Perry, former head of the Child Trauma Academy at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, offers this example of dissociative and hyper-arousal responses in the same child at different times.

"T is a twelve-year-old girl. From birth until age five she lived in a household characterized by domestic violence. During this time, she was noted to be quiet, compliant, "tuned out," daydreamed and generally "a good little girl." She reports little memory of the fighting but her mother describes finding her in her bed, rocking, with covers over her head after some of the fights in the home. At age 12, her mother re-married but unfortunately, episodes of domestic violence resumed in this household. This time, however, T was loud, combative, angry and would run away from the home each time these events took place. She was noted to have "attention" problems at school that turned out to be hypervigilance. Rather than "tuning out" and withdrawing into a dissociative shell, this child was sensitized to fighting and had dramatic and pronounced hyper-arousal during conflict" (Perry, 2000b, p.8).

Hyper-arousal

When a child is exposed to chronic, traumatic stress, his brain sensitizes the pathways for the fear response and literally creates memories such that his fear response becomes almost automatic; he doesn't really think about it. This is called a state of "hyper-arousal." His brain has adapted to a world that is unpredictable and dangerous; it is hyper-vigilant, focused on non-verbal cues that may be threatening (Perry, 1996). The regions of the brain involved in the hyper-arousal response are always "on," and because of this, the child may frequently experience hyperactivity, anxiety, impulsivity, and sleep problems (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995). Hyper-arousal is most common in older children and in males (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995).

In the state of hyper-arousal, similar to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the brain's alarm system becomes particularly sensitive to "threatening" environmental cues, and the child may respond anxiously or aggressively. The regions of the brain involved in the hyper-arousal response become re-activated when the child is exposed to a reminder of the earlier trauma (such as thinking or dreaming about it), to perceived threats (which may not seem threatening to others), and sometimes to generalized reminders (signals) (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995). Perry (1997) presents an example of an 8-year-old boy who became extremely agitated--sobbing and hysterical--when the staff at his group home refused to cut up his hot dog before he ate it. The child had been sexually abused by his father and other men. Foods such as hot dogs, bananas, and popsicles evoked his brain's fear response, and until the "signal" was removed or altered, his brain experienced it as a threat. Another example is that of a child who had committed an impulsive, violent act and explained it by saying, "I could tell he was going to jump me--he looked me in the eyes" (Perry, 1997, p. 6). In his mind, his brain, the simple act of looking him in the eye was perceived as a threat that required a defensive response.

Not only may children in a state of hyper-arousal react anxiously or aggressively to perceived threats, they may actually provoke threatening behavior from others in order to have some control over it. Predictability of threat is important (Perry, 1997). Children who have been victims of unpredictable physical or sexual abuse learn (consciously or unconsciously) that if abuse is going to happen, it is better to control when it happens. They may engage in aggressive, provocative behavior to elicit a predictable response (Perry, 1997). For example, a girl who has suffered repeated sexual abuse from her father may attempt to seduce a male teacher. She may believe that men will invariably try to have sex with her, so she tries to control when and with whom.

Dissociation

While hyper-arousal is more common in older children and males, dissociation is more common in younger children and in females--children who often feel or are immobile or powerless (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995). Dissociation is characterized by first attempting to bring caretakers to help, and if this is unsuccessful, becoming motionless (freezing) and compliant and eventually dissociating; this is often called the "surrender" response (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995). People describe children in a dissociative state as numb, non-reactive, or "acting like they aren't there."

Just as children in a state of hyper-arousal have sensitized neural pathways controlling their response to a threatening environment, children in a state of dissociation have sensitized neural pathways that elicit a different response. A child in a dissociative state, when presented with a threat, may "freeze," both physically and cognitively (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995). When an adult asks or tells them to do something, they don't respond. If the adult becomes angry and more threatening, the child becomes even more anxious and moves further into full dissociation (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995).

Disrupted Attachment Process

At the foundation of much of our development is the concept of "attachment," which refers to the emotional relationships we have with other people. One of the first priorities of an infant is to form an attachment to his primary caregiver (Kraemer, 1992). This relationship not only provides the foundation for future emotional relationships, it also provides the base for other learning, because babies and children learn best when they feel safe, calm, protected, and nurtured by their caregivers. If the attachment process is disrupted, as can occur with abusive and neglectful caretakers, the child's brain will be more focused on meeting his day-to-day needs for survival rather than building the foundation for future growth.

Much of a child's emotional development is rooted in his relationships with his early primary caregivers. For example, it appears that aggressive, submissive, and frustration behaviors may be genetically encoded (Kraemer, 1992). If relationships with the caregivers are positive, the child's cognitive structures learn to regulate these emotions and behaviors. If the relationships are negative or weak, the lower-brain responses become dominant and the cognitive regulating structures do not develop to their full capacity--the young child may neither fully develop the cognitive ability to control his emotions, nor develop an awareness of others' emotions (Kraemer, 1992).

One example of a potential effect of poor early attachments is impaired "social cognition" (Kraemer, 1992). Social cognition involves an awareness of oneself in relation to others and an awareness of the emotions of others. If these abilities are poorly developed, many types of social interactions may be experienced as stressful--unfamiliar, strange situations that are difficult for the child to incorporate because he does not have a strong internal representation (memory) of what is happening and how to respond (Kraemer, 1992). Children who have been abused and neglected often lack empathy and truly do not understand what others feel like when they do something hurtful.

Neglect & Lack of Stimulation

While chronic abuse or neglect can result in sensitized fear response patterns, neglect alone also can result in other problems. Although neglect often is thought of as a failure to meet a child's physical needs for food, shelter, and safety, neglect also can be a failure to meet a child's cognitive, emotional, or social needs. For children to master developmental tasks in these areas, they need opportunities, encouragement, and acknowledgement from their caregivers. If this stimulation is lacking during children's early years, the weak neuronal pathways that had been developed in expectation of these experiences may wither and die, whereupon the children may not achieve the usual developmental milestones.

For example, babies need to experience face-to-face baby talk and hear countless repetitions of sounds in order to build the brain circuitry that will enable them to start making sounds and eventually say words and form sentences (Helgeson, 1997). If babies are ignored, if their caregivers do not provide this type of intense verbal interaction, their language development may be delayed. If a child does not receive kindness as an infant, he may not know how to show kindness as an adult. If a child's cries for attention are ignored as a toddler, he may not know how to interact positively with others later. These capacities may not fully develop because the required neuronal pathways were not activated enough to form the "memories" needed for future learning (Greenough, Black & Wallace, 1987).

Global Neglect

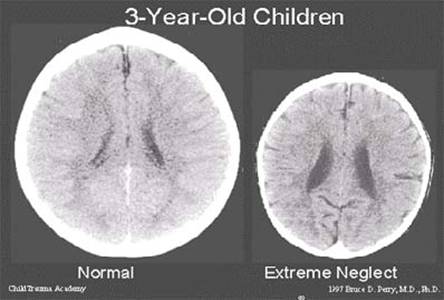

The term "global neglect" is used when a child has experienced deprivations in more than one domain, e.g., language, touch, and social interaction (Perry & Pollard, 1997). Children who were adopted from Romanian orphanages in the early 1990s are often considered to be globally neglected; they had little contact with caregivers and little to no stimulation from their environment--little of anything required for healthy development. One study found that these children had significantly smaller brains than the norm, suggesting decreased brain growth (Perry & Pollard, 1997). (See Figure 1.)

This type of severe, global neglect can have devastating consequences. The extreme lack of stimulation may result in fewer neuronal pathways available for learning; genetically normal children may be at a permanent intellectual disadvantage (Greenough, Black & Wallace, 1987). The lack of opportunity to form an attachment with a nurturing caregiver during infancy may mean that some of these children will always have difficulties forming meaningful relationships with others (Perry, 2001a). But these studies also found that time played a factor--children who were adopted as young infants have shown more recovery than children who were adopted as toddlers (Rutter, et al., 2000).

|

Figure 1 |

Pervasive & Long-term Effects

Maltreatment during infancy and early childhood has been shown to negatively affect early brain development and can have enduring repercussions into adolescence and adulthood. As mentioned earlier, the experiences of infancy and early childhood literally provide the organizing framework for the expression of children's intelligence, emotions, and personalities. When those experiences are primarily negative, children may develop emotional, behavioral, and learning problems that persist throughout their lifetimes, especially in the absence of targeted interventions.

While some children seem unaffected or minimally affected by their traumatic experiences, in reality, it is often the adults around them who are misreading their cues. These children are communicating non-verbally with us, and we need to learn the language and educate others who work with children who have been maltreated about this language (Perry, 1999). Children do not just "get over it." As they attempt to cope, as their brains adapt to the negative environments, their true emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and social potential may be diminished (Perry, Pollard, Blakely, Baker & Vigilante, 1995).

Children who have experienced chronic abuse and neglect during their first few years may live in a persistent state of hyper-arousal or dissociation, anticipating threats around every corner, and their ability to benefit from social, emotional, and cognitive experiences may be impaired (Perry, 1996). The various regions of the brain cannot grow without being activated, and certain regions cannot be activated when others are. To learn and incorporate new information, whether it be a lesson in the classroom or a new social experience, the child's brain must be in a state of "attentive calm," a state the traumatized child rarely achieves. It is not uncommon for teachers who work with traumatized children to observe that the children are really smart, but do not learn easily; they are often diagnosed with learning disabilities (Perry, 1996). Children who have not been able to develop healthy attachments with their caregivers, and whose early emotional experiences have not laid the necessary groundwork for healthy emotional development, may have a limited capacity for empathy (Perry, 1997). The ability to feel remorse and empathy are built on experience. In the extreme, if a child feels no emotional attachment to any human being, he cannot be expected to feel remorse for hurting or even killing someone. Perry (1997) offers the example of a 15-year-old boy who felt no remorse for having committed murder. The boy had been neglected and humiliated by his primary caretakers as a child. "He is literally emotionally retarded. The part of his brain which would have allowed him to feel connected to other human beings--empathy--simply did not develop" (Perry, 1997, p. 4).

The effects of abuse and neglect on the developing brain during children's first few years can result in various mental health problems. For example:

- Diminished growth in the left hemisphere may increase the risk for depression (Teicher, 2000).

- Irritability in the limbic system can set the stage for the emergence of panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Teicher, 2000).

- Smaller growth in the hippocampus and limbic abnormalities can increase the risk for dissociative disorders and memory impairments (Teicher, 2000).

- Impairment in the connection between the two brain hemispheres has been linked to symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Teicher, 2000).

- Severely neglected children who have been deprived of sensory stimulation--including touch, movement, and sound--may be at risk for Sensory Integration Disorder (SID) (Parent Network for the Post-Institutionalized Child, 1999).

- Children who have been raised in environments that totally disregarded their needs for comfort, stimulation, and affection may be at risk for Reactive Attachment Disorder (Parent Network for the Post-Institutionalized Child, 1999).

We are learning more about the serious, long-term consequences of abuse and neglect on brain development, and subsequent physical, cognitive, emotional, and social growth. What do we do with this information? What does it mean for biological parents, foster and adoptive parents, professionals, the child welfare system, and for society? How can we use this knowledge to improve our interventions with children who have been abused and neglected, and, most importantly, to prevent abuse and neglect from occurring? While these questions may be challenging, this growing body of knowledge compels us to work toward finding the answers.