A Conceptual Frame for Developing the “Zone of Respectful Rigor” (ZRR) for Learners

Consider the situation we are all now faced with in education.

As individual educators move more deeply into implementing the CCSS, care is being taken to reflect on the pedagogical strategies that help create deep connections for learners. Learner engagement is of utmost importance, and equally important is the need to monitor for signs of disengagement. Somewhat paradoxically, disengagement can come from unrealistic levels of rigor (“too hard”) as much as they can come from levels of rigor so low as to produce boredom (“too easy”).

As systems move into deeper implementation of the CCSS, it will be increasingly important to stay connected with learners so that their perspective is at the forefront. Like any good parent who attends to the affective needs of his child during a move or significant transition, educators must develop a Common Core mindset that balances various elements of “the big move” to the CCSS. Simply put, the move will not be successful if the "parent" and the "stuff" arrive—but the child doesn't.

The intersection of these shifts occurs as individual teachers engage individual students in a systematic way to determine each learner’s “zone of respectful rigor” (ZRR).

While we can clearly see the inequity of results (e.g. through data), we need to be open to learning how inequity inputs, or learning conditions, play a role in achieving those results. A clear example of an inequity occurs when educators ignore the legitimate needs of a learner attempting to access vital content. To the extent that any learner is not provided the conditions needed for her to learn, evidence will be produced of deficiencies in the learning conditions themselves, not necessarily in the learner. Similarly, aiming at standards-based content that is clearly too advanced for a learner will reveal that the learner does not have a legitimate shot at being successful.

Understanding learner variance and working to design variant learning conditions (commonly referred to as “differentiating instruction”) are integral to successful implementation of the CCSS. Simply put, you can and should differentiate your approach while simultaneously embracing standards.

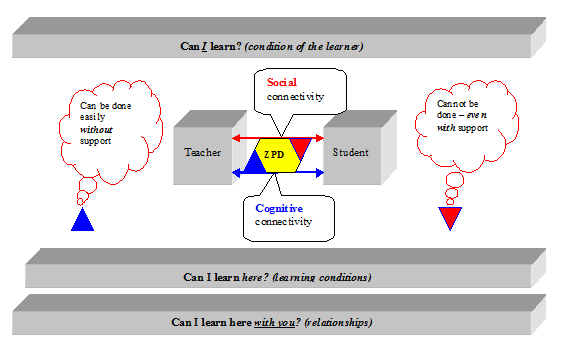

As teachers know, the diversity in a typical mixed-ability classroom requires that they be prepared to address the level of difficulty experienced as a result of the rigor present. For many, Vygotsky's notion of a "zone of proximal development" (ZPD) will be useful in making sense of rigor within the CCSS. In Vygotsky's learning theory, the role of the teacher is to support learners at the level at which they cannot perform or learn independently and require the expertise of a more competent learner to guide them.

Therefore, teachers need to exercise caution and refrain from setting levels of rigor that are beyond those at which students can experience success. If the level of rigor is too advanced or is inaccessible even with support, then achievement at that level is unlikely. The standards are the standards, but each student's experience of that rigor provides a context. This may be counterintuitive because so much attention has been given to the need for rigorous, standards-based learning. But in order for it to be "standards-based learning," learning must indeed take place, and that learning should be aligned with the standards.

Educators must see learning conditions as either being respectful of the learner’s current context, or not (i.e., disrespectful). When tasks are disrespectful—the learner sees only the difficulty in learning. Such learning difficulty must always be understood through the eyes of learners themselves. One way to reflect on this is to simply ask yourself, “What is it like to be a learner in my own classroom?” For students with particular challenges, it may be more helpful to ask, “What is it like to be this learner in my classroom?”

Engagement as a Construct

For many, framing student engagement in the context of Lev Vygotsky’s (1978) “zones of proximal development” will make a great deal of sense. In Vygotsky’s view, the role of a teacher (or parent) during the learning process was to act as a “knowledgable other” or guide for a learner. Vygotsky emphasized that when the learner could do many things independently, no new learning was taking place. On the other hand, some tasks were too difficult even with support from a knowledgeable adult. The task of teachers was to determine the space between these two boundaries and bridge the gap for learners.

In order to see how these concepts might play out between a teacher and a student, consider the three questions every learner asks from within a ZPD framework:

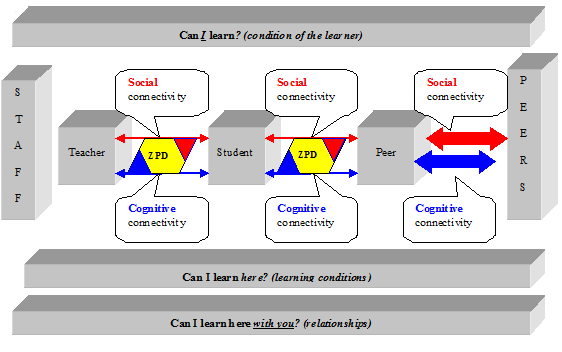

Many different applications of Vygotsky’s theories have been made. For the purposes of this course, it is helpful to draw attention to the social nature of the ZPD in conjunction with the standards-based application of rigor. The concept of ZPD is instrumental even if it is applied only to a discussion of student academic readiness. What can be overlooked is the social nature of the learning process that assumes the interaction between two individuals. The ZPD is something that emerges through the way the more knowledgeable adult knows the student. As a teacher helps to bridge the span between the blue triangle and the red triangle, the ZPD assumes an ongoing relationship or conversation.

Another important aspect of applying Vygotsky’s ZPD is that the framing and re-framing of a student’s ZPD is a recursive process, not an event. Because it is a dynamic process of constant reframing the student’s needs it assumes the teacher’s role will be one of constant re-design so that the student experiences success within his zone. The reason the zone is “proximal” is that it has been determined at each step of the way that adult support is essential for the learning progression to continue. As such, teachers cannot use “one size fits all” approaches or disengage from learners.

Because knowledge is constructed through social relationships, not in spite of them, the learner also develops positive affiliations with the teacher. In other words, trust is developed that the teacher is interested in and attentive to the learning needs of the student. The relationship helps to mediate the relevance and the rigor. It is nearly impossible to differentiate instruction for someone you truly do not know. Likewise, it is hard for a teacher to gain an in-depth perspective on a learner’s interests if the teacher has not taken an interest in the individual to begin with. Relationships mediate the relevance and rigor of what is being engaged.

Each day, numerous situations arise wherein teachers are making real-time adjustments for learners so that the level of rigor can be maximized for each student. In the area of CCSS ELA/Literacy, this occurs regularly as students are challenged with complex text, close reading activities, and engagement with text-dependent critical thinking questions (for example).

With these variables in mind, we can begin to frame a working definition of engagement that supports each student’s engagement from within her “zone of respectful rigor”(ZRR).

Engagement is:

- anything occurring situationally (immediate learning conditions)

- that has cognitive content (e.g., skill, knowledge, information)

- with social dimensions (relationship)

- requiring a shared focus (attention)

- with value or a future purpose (intention)

and answers the questions every learner asks:

- Can I learn?

- Can I learn here?

- Can I learn here with you?

Moving from a Teaching Mindset to a Learning Mindset

One of the most significant shifts occurring in education today is a full consideration of what it is like to be a learner within any given learning environment. Under a constructivist approach, it is assumed that all learners are motivated and work to create meaning within the various contexts they experience. The real question is whether professionals have engaged learners enough to know what is best from the perspective of the learner.

This point of perspective taking (i.e., imagining we are now the “customer”) is more than a cognitive exercise. It is a point that has been summarized by leading experts on effective teaching, including Charlotte Danielson and Robert Marzano. Consider the following selected quotes to better understand the significance of considering the nature of the shift occurring in education.

The most significant research finding is deceptively simple: Learning is done by the learner. That is, as teachers we tend to think that our students learn on account of what we do. But that is a mistake: Our students don’t learn because of what we do; they learn because of what they do. Our challenge then is to design learning experiences for students that are interesting and that yield the learning we desire (Danielson, 2009, p. 36).

And Marzano, Pickering, and Heflobower’s (2010) sentiments are reflected in a recent work on student engagement:

At the core of our model are the four emblematic questions that were used to organize the research and theory:

- How do I feel?

- Am I interested?

- Is this important?

- Can I do this? (p. 19)

As we saw in chapter 1, a student’s answer to the emblematic question “How do I feel?” is a composite of three factors: the student’s level of energy, the demeanor of the teacher, and the student’s perception of acceptance by the teacher and peers. If a student has little energy, he or she most likely will not attend to what is occurring in class. If a teacher’s general demeanor establishes a negative or overly serious affective tone, the student most likely will not attend to what is occurring in class. Finally, if a student does not feel accepted by the teacher or by peers, he or she will most likely not pay attention in class (p. 21).

As these quotes by leading educational researchers and theorists suggest, the emphasis on understanding the perspective of students is unmistakable. The goal of all engagement with learners is not “rigor at all costs”; rather, rigor must be offered respectfully by looking at it differently, namely by asking, “At what cost, rigor?” A teaching mindset best describes situations in which information has been delivered, though unprocessed and unapplied by learners. A learning mindset is oriented toward the learner’s perspective and asks that regardless of what methods are needed, the methods best suited to the student are applied so that learning conditions are optimal.

Seen in this way, we should look at rigor through the lens of a relationship… and not only the teacher-student relationship, but the myriad of relationships experienced by learners in schools every day. Consider the following visual graphic that helps illustrate these variables:

If we are asking students to be “highly engaged” when they lack sufficient conditions, either

(a) internally (stressed, hungry, angry, fearful, alienated, confused, or lack prior knowledge) OR

(b) externally (a myriad of reasons including unrealistic levels of rigor points determined by their teacher)—then rigor can become a trigger for disengagement.

As educators, we must attend to the learning conditions that affect learners. We must leave no doubt in the learner’s mind that our aim is to design learning conditions that are conducive to learning, and this includes the level of rigor we as educators determine to be appropriate, or a “zone of respectful rigor” (ZRR). This determination is best made through knowing each student well enough to make such a determination.

As practitioners move toward deeper implementation of the Common Core, it will be important to remember that standards—by themselves—are just standards. It is in the context of meaningful relationships with caring educators that standards-based determinations associated with rigor can best be made.