Trauma & Terror in Childhood:

The Neuropsychiatric Impact of Childhood Trauma

Bruce D. Perry, M.D., Ph.D.

Child Trauma Academy

Pre-final Draft

Childhood can be a very dangerous time. Each year in the United States alone more than 5 million children experience some form of traumatic experience (see Pfefferbaum, 1997, 1998; Perry, 1994, 2000). Traumatic stress can have profound impact on the emotional, behavioral, cognitive, social and physical development of children, in some cases resulting in lifelong loss of potential and chronic mental and physical health problems. These injuries cost the individual, the family, the community and, ultimately, society.

For: "Handbook of Psychological Injuries: Evaluation, Treatment and Compensable Damages" (Ed., I. Schulz, S. Carella & D.O. Brady) American Bar Association Publishing. August 20, 2000.

The Brain, Stress & Adaptation

Our brain is designed to sense, process, store, perceive, and act on information from the external and internal world to keep us alive. In order to do this, our brain has hundreds of neural systems, all working in a continuous, dynamic process of modulating, regulating, compensating -- increasing or decreasing activity to control the body's physiology. Each of our many complex physiological systems has a rhythm of activity that regulates key functions. When blood sugar falls below a certain level, a set of compensatory physiological actions is activated. When tissue oxygen is low from exertion, when an individual is dehydrated, sleepy, or threatened by a predator, still other sets of regulating activity will be turned on to respond to the specific need. For each of these systems there are “basal” or homeostatic patterns of activity within which the majority of environmental challenges can be sustained. When an internal condition (such as dehydration) or an external challenge (an unpredictable and unstable employment situation) persists, this is a stress on the system.

Stress is any challenge or condition that forces the regulating physiological and neurophysiological systems to move outside of their normal dynamic activity. Stress occurs when homeostasis is disrupted (see Perry & Pollard, 1998). Traumatic stress is an extreme form of stress.

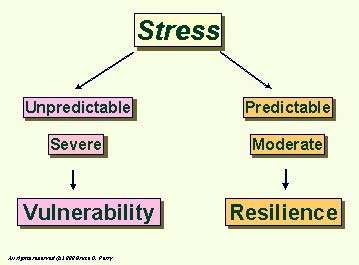

It is important to understand that stress during development is not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, the development of stress-response neural systems depends upon exposure to moderate, controllable levels of stress. The opportunity for a toddler to control his or her exploration, to discover and to experience moderated novelty is essential for healthy development. Children, when given the opportunity for moderate, controlled exposures to stress during childhood – with a consistent, available and safe caregiver to serve as "home-base," can become inoculated against future, more severe stressors. Moderate, predictable levels of arousal and "stress" related to the novelty of healthy exploration and development help create a resilient, healthy child.

With this said, however, dramatic, rapid, unpredictable, or threatening changes in the environment will activate the “stress” response systems. These brain-mediated responses recruit a set of central and peripheral nervous system, neuro-endocrine, and immune responses that promote adaptive “survival” functions and, later, a return to equilibrium or homeostatic patterns. Events that disrupt homeostasis are, by definition, stressful. If this stress is severe, unpredictable, prolonged, or chronic, the compensatory mechanisms can become over-activated or fatigued, and incapable of restoring the previous state of equilibrium or homeostasis. The physiological system re-organizes its “basal” patterns of equilibrium. An event is “traumatic” if it overwhelms the organism, dramatically and negatively disrupting homeostasis. In a very real sense, trauma throws the organism “off balance,” and creates a persisting set of compensatory responses which create a new, but less functionally flexible state of equilibrium. This new, trauma-induced homeostasis is more energy consuming and maladaptive than the previous state. By inducing this "expensive" homeostasis and compromising full functional capability, trauma robs the organism. It has survived the traumatic experience, but at a cost.

Threat & Adaptive Responses

Arousal Response

The human body and human mind have a set of very important and very predictable responses to threat (for review see Perry, 1994; 1998; 1999). Threat may come from an internal (e.g., pain) or external (e.g., an assailant) source. One common reaction to danger or threat has been labeled the “fight or flight” reaction. In the initial stages of this reaction there is a response called the alarm reaction.

As the individual begins to feel threatened, the initial stages of a complex, total-body response will begin. The brain orchestrates, directs, and controls this response. If the individual feels more threatened, their brain and body will be shifted further along an arousal continuum in an attempt to ensure appropriate mental and physical responses to the challenges of the threat. The cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning of the individual will reflect this shift along the arousal continuum. During the traumatic event, all aspects of functioning of the individual change – feeling, thinking, behaving -- all change. Someone being assaulted doesn't spend a lot of time thinking about the future or making an abstract plan for survival. At that moment, their thinking, behaving, and feeling are being directed by more “primitive” parts of the brain (see Table 1). A frightened child doesn't focus on the words; he or she attends to the threat-related signals in the environment – the non-verbal signs of communication such as eye contact, facial expression, body posture, or proximity to the threat. The internal state of the child shifts with the level of perceived threat. With increased threat a child moves along the arousal continuum from vigilance through to terror.

The alarm continuum is characterized by a graded increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, in turn causing increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration; a release of glucose stored in muscle; and increased muscle tone. Changes in the central nervous system cause hyper-vigilance; the child tunes out all non-critical information. These actions prepare the child to fight with, or run away from, the potential threat. This total body mobilization, the "fight or flight" response, has been well characterized and described in great detail for adults. These responses are highly adaptive and involve many coordinated and integrated neurophysiological responses across multiple brain areas such as the locus coeruleus, the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the brainstem nuclei responsible for autonomic nervous system regulation.

What does hyper-arousal really mean?

Hyper-arousal is a multi-dimensional process, characterized by both mental and physical changes. These include an increase in the activity of those parts of the central and peripheral nervous system responsible for the perception and processing of potentially threatening information. This graded response also involves "action." During the hyper arousal process, many physiological systems required for survival are activated (e.g., stress response hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline). The many physiological changes during hyper-arousal will influence the way a person thinks, feels and acts.

Dissociation

The most well characterized reaction to threat is the "fight or flight" response. A second common reaction pattern to threat is dissociation. It is increasingly clear that responses to threat can vary tremendously from individual to individual. This second major adaptive response to threat involves an entirely different set of physiological and mental changes, yet does not fall under the heading of either "fight" or "flight." Dissociation is not always a response to threat or trauma, though. It is a common mental mechanism used in many situations during a routine day. For example, meditation, Lamaze childbirth exercises, daydreaming, and highway hypnosis are all mild forms of dissociation. Many common and "normal" mental states such as anxiety, dissociation, or anger are experienced by most of us to some degree. When any one of these becomes pervasive and ever-present, however, it begins to interfere with the rest of one's life. When this occurs, we often classify this problem as a neuropsychiatric disorder.

Differential Response to Threat |

|

Dissociation |

Hyper-arousal |

|

|

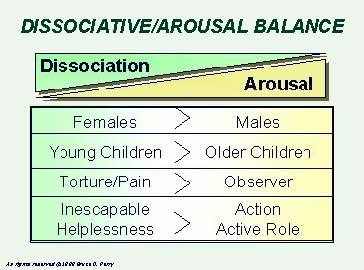

Children tend to use dissociation as an adaptation to threat more often than adults. Because of their small size and limited life experiences, "fight or flight" is usually not an option for children in a threatening situation. When fighting or physically fleeing is not possible, the child may use avoidant and psychological fleeing mechanisms that are categorized as dissociative. Dissociation due to threat and/or trauma may involve a distorted sense of time, a detached feeling that you are "observing" something happen to you as if it is unreal, the sense that you may be watching a movie of your life. In extreme cases, children may withdraw into an elaborate fantasy world where they may assume special powers or strengths.

Like the alarm response, this "defeat" or dissociative response is graded along a continuum. The intensity of the dissociation varies with the intensity and duration of the traumatic event. Again, remember that even when we are not threatened, we use dissociative mental mechanisms, such as daydreaming, all of the time. The period between wakefulness and sleep is another example of dissociating from the present to one’s inner thoughts, ideas, fears, fantasies, and then, ultimately, moving into the state of sleep. During a traumatic event, all children and most adults use some degree of dissociation. However, some individuals will use, and some kinds of trauma induce, dissociation as a primary adaptive response.

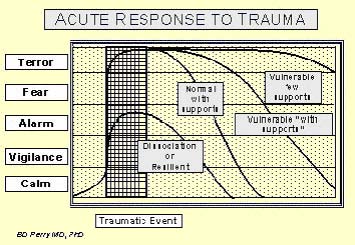

For most children and adults, however, the adaptive response to an acute trauma involves a combination of hyper-arousal and dissociation. During the actual trauma, a child will feel threatened and the arousal systems will activate. With increased threat, the child moves along the arousal continuum. At some point along this continuum, the dissociative response is activated. This results in a host of protective mental (e.g., decreases in the perception of anxiety and pain) and physiological responses (decreased heart rate: see Perry et al., 1995) that characterize the dissociative response (see Differential Response to Trauma figure, above).

- The brain mediates threat with a set of predictable neurobiological, neuro-endocrine, and neuropsychological responses.

- These responses may include different “survival” strategies -- ranging from fighting or fleeing to “giving up” or a “surrender” reaction.

- There are multiple sets of neurobiological and mental responses to stress. These vary with the nature, intensity, and frequency of the event. Different children may have unique and individualized “response sets” to the same trauma.

- Two primary adaptive response patterns in the face of extreme threat are the hyper-arousal continuum (defense -- fight or flight) and the dissociation continuum (freeze and surrender response). Each of these “response sets” activates a unique combination of neural “systems.”

- These response patterns are somewhat different in infants, children and adults -- though they share many similarities. Adult males are more likely to use a hyper-arousal (fight or flight) response -- young children are more likely to use a dissociative pattern (freeze and surrender) response.

- As with all experience -- when the brain “activates” the neurophysiological systems associated with alarm or with dissociation, there will be use-dependent neurobiological changes (or in young children, use-dependent organization) which reflects this activation.

- It is these use-dependent changes in the brain development and organization which underlie the observed emotional, behavioral, cognitive, social, and physiological alterations following childhood trauma.

- In general, the predominant adaptive style of an individual in the acute traumatic situation will determine which post-traumatic symptoms will develop – hyper-arousal or dissociative.

Effects of Fear

How Fear Changes Thinking, Feeling & Behaving |

|||||

Hyper-arousal Continuum |

REST | VIGILANCE | RESISTANCE Crying |

DEFIANCE Tantrums |

AGGRESSION |

Dissociative Continuum |

REST | AVOIDANCE | COMPLIANCE Robotic/detached |

DISSOCIATION Fetal Rocking |

FAINTING |

| Regulating Brain Region | NEOCORTEX Cortex |

CORTEX Limbic |

LIMBIC Midbrain |

MIDBRAIN Brainstem |

BRAINSTEM Autonomic |

| Cognitive Style | ABSTRACT | CONCRETE | EMOTIONAL | REACTIVE | REFLEXIVE |

| Internal State | CALM | AROUSAL | ALARM | FEAR | TERROR |

Table 1: How Fear Changes Thinking, Feeling and Behaving: Different children have different styles of adaptation to threat. Some children use a primary hyper-arousal response, some a primary dissociative response. Most use some combination of these two adaptive styles. In the fearful child, a defiant stance is often seen. This is typically interpreted as a willful and controlling child. Rather than understanding the behavior as related to fear, adults often respond to the “oppositional” behavior by becoming angrier and more demanding. The child, over-reading the non-verbal cues of the frustrated and angry adult, feels more threatened and moves from alarm to fear to terror. These children may end up in a primitive "mini-psychotic" regression or in a very combative state. The behavior of the child reflects their attempts to adapt and respond to a perceived (or misperceived) threat.