An Introduction to UDL Applications

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a theoretical framework developed by CAST (the Center for Applied Special Technology) to guide the design and development of learning environments that represent materials in flexible ways and offers a variety of options for learners to comprehend information, demonstrate their knowledge and skills, and be motivated to learn (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014; Hall, Meyer, & Rose, 2012; CAST, 2011; Rose, Meyer, & Hitchcock, 2006; Pisha & Coyne, 2001; Rose, 2001; Rose & Dolan, 2000; Rose & Meyer, 2000a, 2000b, 2002; Rose, Sethuraman, & Meo, 2000). The concept of UDL was inspired by the universal design movement in architecture. This movement calls for the design of structures that anticipate the needs of individuals with disabilities and accommodate these needs from the outset. Universally designed structures are indeed more usable by individuals with disabilities, but in addition they offer unforeseen benefits for all users. Curb cuts, for example, serve their intended use of facilitating the travel of those in wheelchairs, but they are also beneficial to people pushing strollers, young children, and even the average walker. And so, the process of designing for individuals with disabilities has led to improved usability for everyone.

The universal design movement changed how architects think about designing buildings. Similarly, UDL calls for a shift in how educators think about designing learning environments. Traditional curricula in printed text and new curricula that incorporate inaccessible digital technology present a host of barriers that limit learners’ access to information, ability to express knowledge, and ability to be engaged in learning. With printed text, learners without a well-developed ability to see, decode, attend to, or comprehend printed text are compelled to adapt to its ubiquity as best they can. Similarly, if new curricula in a digital medium are not fully accessible from the start, not all learners will be able to navigate, interact, comprehend, or express their knowledge.

What is even more detrimental to learning is that fixed, one-size-fits-all curricula are designed and developed to address the needs of mainstream learners and, consequently, disregard the diversity in skills, needs, and interest that individuals bring to learning. In contrast, a UDL curriculum is designed and developed to take full advantage of the inherent variability in individual learners. As a result, a UDL curriculum is innately flexible, enriched with multiple media so that many paths are provided to develop the talents of all learners. In doing so, a UDL curriculum reduces barriers as well as optimizes the level of challenges and supports to meet the needs of learners from the start.

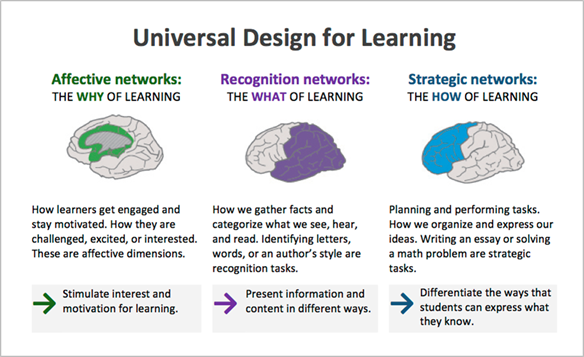

The UDL framework is based on neuroscience research evidence that individual learners differ in the ways in which they are motivated (affective network), how they comprehend information (recognition network), and how they express what they know (strategic network). Whether the differences facilitate learning or become a detriment to learning depends largely on the educational context. If a learning environment is flexible and can be adjusted to match an individual’s strengths, then a characteristic that is a deficit in one learning context becomes an asset in another. The characteristics of a learner and the curriculum are not fixed entities, but continuously evolve together as the learner grows and progresses. As Meyers, Rose, and Gordon explain, “Success occurs when the learner and the curriculum interact in ways that help them both improve at the same time” (2014).

To guide educators in creating lessons, curricula, and learning systems that are engaging, maximize flexibility, and optimize learning, the three primary brain networks are translated into three UDL principles of design: 1) provide multiple means of engagement, 2) provide multiple means of representation, and 3) provide multiple means of action and expression (see Figure 1) (Rose, Meyer, & Gordon 2014).

Figure 1. The three primary brain networks and their relation to UDL.

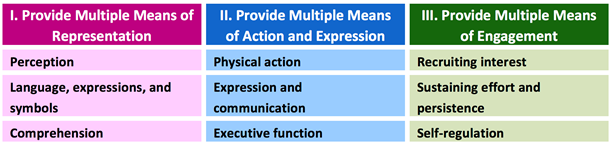

The three UDL principles call for flexibility in relation to three essential facets of learning, each one orchestrated by a primary brain network. Each UDL principle is then expanded into UDL guidelines and checkpoints. The depth and comprehensiveness of the UDL guidelines can guide educators to build flexibility into all components of a curriculum—goals, methods, materials, and assessment—so that all students are supported in their access, participation, engagement, and ongoing monitoring of progress across all facets of learning.

Although the three primary brain networks that facilitate learning are described separately, they are in fact highly interconnected and continuously work in concert. Similarly, the components of a curriculum—goals, assessment, methods, and materials—are most effective when they are aligned. The flexibility that is at the core of a UDL curriculum is the result of crafting goal statements that avoid prescribing a particular way to achieve them. Learning goals that separate the means from the end provide educators the flexibility to include a variety of teaching methods and materials that can be adjusted to match student needs and strengths. For example, if the learning goal is for students to understand a specific content piece then multiple options can be built into the curriculum for students to interact with that content (recognition network), for them to demonstrate their understanding of it (strategic network), and to engage and sustain their motivation in learning (affective network). Additionally, to make appropriate adjustments during the course of instruction requires assessments that are ongoing, measure student progress, and capture student interactions with the curriculum. In a UDL curriculum, formative assessment, which is employed during instruction to monitor student progress and inform instructional decisions, is more valuable than summative assessments that measure student performance after the completion of instruction. Likewise, digital curricula that log student actions and then generate visual reports of students’ paths through a curriculum overtime is more valuable than traditional curricula that don’t capture student interaction with the curricula. Designing curriculum that adheres to the UDL principles insures that the goals, methods, materials, and assessments work seamlessly together to optimize learning.

One of the most essential ingredients of an effective curriculum is engaging students in learning. In a UDL curriculum, involving students in the process of setting a learning goal is as critical to its achievement as the goal statement itself. Having students re-state goals in their own words, asking students for feedback about goals, and supporting students in setting goals for themselves are all critical to developing their self-efficacy and engagement in learning. Providing a rich array of materials and multiple paths to reach a goal not only recruits student interest and motivates them to learn but also provides opportunities for them to explore and develop their own interests. It is invaluable for educators to have immediate access to assessment information that they can use to inform instructional decisions as they are teaching. Similarly, involving students in monitoring their own progress by sharing information about their own learning behaviors and performances is empowering. When students view their own information, they ask and find answers to questions about themselves. What I am I doing? What is working? What can I improve? Thus assessment that is analyzing the identifying components often a source of anxiety and stress becomes an opportunity to practice self-regulation skills and develop self-efficacy, key factors of motivation in learning.

Figure 2. Three primary principles guide UDL—and provide structure for the Guidelines.

To help teachers support learners’ diverse recognition, strategic, and affective networks CAST has developed three sets of UDL teaching methods. These teaching methods can be used to make curricula more flexible and broadly supportive.